What is a Good Format?

If you’ve visited any online community at any point while playing the game, you probably noticed people complaining about the format. Whether its Lusamine, Zoroark-GX, Mewtwo-EX, Guzma, or Garbodor, if you take a top tier card, you’ll find someone claiming it ruins the game and/or calling for its ban. Players will complain about a format, longing for the good days of X years before. X years later, though, they’ll complain about the new current format, and look back favorably about the one they used to complain about.

Is the game on an endless downwards spiral? No. Back in 2012, in a thread wondering if the current format was the worst ever, Kyle “Pooka” Sucevich (who was still playing at the time) wrote, “The worst format is always the one we are playing currently.” This makes sense: it’s far easier to see the bad parts of a format when you’re playing in it. If you lose a game because you got hit by Marshadow‘s Let Loose on turn 1 and drew nothing, it will sting; you might complain to your friends, in between rounds, that you got unlucky; if it happened in the win-and-in round of a League Cup, it might ruin your day. Given enough League Cups and enough Marshadow, there will always be someone, somewhere, to live out this scenario. A person who went looking for opinions on the Internet would see many people complaining about Marshadow and the format. Years later, distanced from the pain of turn 1 Let Loose, players will remember fonder memories, the time they outplayed their opponent by playing around their Beast Ring turn, or the fun they had sequencing their moves when playing Granbull.

Another explanation is that some people will always find something to complain about, maybe to find something to blame their losses on, other than their own mistakes. I lost because Zoroark-GX is overpowered, and not because my deck is poorly built or because I carelessly discarded Stadiums I would need later in the game.

That said, it would be silly to conclude that this explains all the complaining about whatever the current format is. It would be naive to imagine that every format is as good, or that there has never been any mistake in the game’s design. Every player will remember times when they had more or less fun playing the game. There is subjectivity in this, of course: maybe one person enjoyed a specific format because that’s when they first made day 2 at a Regional Championship, or because they finally found success with a rogue deck. However, I don’t think that’s all there is to it. There are many Pokémon players who enjoy playing, and building decks for, old formats, and among these old formats, some are remembered with far more fondness than others. I’ve seen many more people wanting to play the format from Worlds 2010 than 2012, for example — myself included.

I’ve been playing the Pokémon TCG for ten years. In that time, I’ve seen my share of formats, of complaints about these formats, and of arguments about whether some previous format was better. its also a topic about which I’ve thought a lot, so in this article, I’d like to explore what makes some formats more fun or interesting to play — or, to put it bluntly, better — than others. I acknowledge that there’s a part of subjectivity in what people enjoy, but I will try to get to the core behind that layer of subjectivity.

What is the point of this article? Obviously, I don’t expect it to reach the card designers in Japan, so it won’t have an effect on the future of the game. It can be useful to people designing an alternate format such as a cube draft. However, for the most part, I think its an interesting topic. As both a long time fan and a semi-professional player of the Pokémon TCG, I spend a lot of time thinking about the game and the design behind it. I like to believe that I’m not a simple consumer of a product, but a theoretician of an admittedly narrow field. Astronomers look at stars in the night sky and predict their movements. I play Pokémon and try to understand why playing Zoroark-GX is better than not playing Zoroark-GX. It’s basically the same thing.

I often try, in my writing, to bring some attention to this way I look at the game, but its usually a side note in an article on another topic. This time, this is all about it.

Let’s Talk About Game Design

From one set to another, the game may get more or less interesting, depending on what cards and decks get played. What gets played, though, is not an accident, but a direct result of the game’s design. Of course, the designers may not anticipate the whole metagame, and I’m sure some of the decks that made a dent in the metagame came as a surprise even to them (was Ultimate Mewtwo and Mew-GX planned? Probably not.) Still, what a format looks like, broadly speaking, depends on what the designers wanted it to be. Therefore, we should look at how sets are designed.

I don’t think there are enough conversations about the Pokémon TCG’s design. When a new card is revealed, there are several ways to look at it. Most players, and content creators in the Pokémon TCG community, will look at it from a competitive standpoint: will this card see play? Can it fit into an existing deck archetype, spawn a new one, be used as a tech against some deck or strategy? Usually, one does not look at a card alone, but in relation to its environment: your take on Zacian V will be different whether or not you notice it came out at the same time as Metal Saucer. None of this is wrong, but it’s only looking at the result, and not at the intent behind the card.

In modern TCGs, game designers will often be more transparent about their goals. Whenever a new set, or a balance patch, comes out, they will explain why they wanted to promote some new game mechanic, what flavor they were trying to evoke with some cards, why deck X needed a nerf, etc. In Pokémon, though, there is no such communication, which means its up to players to make their own opinions about what each set is supposed to mean.

I’ve never been a competitive player in some other large TCGs, but I used to watch international championship streams of other games, so I was always interested in the game, even if from afar. I learned a lot about it by reading Jesse Mason, a self-titled game design critic who wrote comprehensive reviews of sets from other TCGs from a holistic perspective: looking at the themes and inspirations behind each set (or, to be more accurate, each block of sets), it’s aesthetic, how the cards played both in Constructed and Limited (drafts are an important part of other games, unlike Pokémon), etc. His writing led me to think about Pokémon in similar ways, and keeps being an inspiration for me.

Admittedly, there is not as much to comment on in most Pokémon sets. There usually isn’t even a theme underlying them. Most of the Pokémon from Plasma Freeze are depicted in environments that look unnaturally frozen, as a reference to the events of Black and White 2, in which Team Plasma freezes an entire city thanks to Kyurem. That’s cool to look at and makes the cards from this set stand out visually from other ones, but it changes absolutely nothing from a gameplay perspective. Remove the illustrations, and there’s nothing that lets you tell apart cards from Plasma Freeze from cards from, say, Plasma Blast (or Next Destinies, or Furious Fists, honestly, apart from the presence of Team Plasma Pokémon*). For the most part, new sets rarely introduce new mechanics, so the game tends to play mostly the same, at least in theory.

* There are times when cards do reference things from the rest of the Pokémon canon beyond their name and illustration, something that other card games can’t do, and those rare cards are absolutely wonderful, in my opinion. For example, First Impression and Crossing Cut GX make Golisopod-GX play in a way that encourages players to get it repeatedly in and out of the Active spot, which mimics how Golisopod plays in the video game. It also works well with Guzma for this reason, which helps to reference its status as Guzma’s signature Pokémon in the video game. This is achieved elegantly, without having to directly reference one card on the other’s text, unlike, say, Garchomp and Cynthia.

In practice, though, even though new sets rarely feel revolutionary, the game changes a lot from one format to another. This is because in Pokémon, more than other games, decks are built around one specific card or combination of cards, rather than a general concept, thanks to all the card draw and search in the game. It’s also more frequent for one card to end up in multiple decks. Therefore, individual cards can have a huge effect on the game; think of how Mewtwo-EX, Seismitoad-EX, or Zoroark-GX all made the game revolve around them, at least for a time.

Enough comparison with other games, though. its time to look at how Pokémon was designed in the last ten years.

A Short History of the Pokémon TCG Since Black and White

The game has been around for far more than ten years, but in this section, I’ll only talk about how the game changed since the 2011-2012 season, for two reasons. First, this was the HeartGold SoulSilver-on season. I started playing in 2010, when HeartGold SoulSilver was the latest released set. Therefore, when the Standard format rotated from Majestic Dawn-on in September 2011, for the first time, I was familiar with every card in the format, having been around when they were released. While I do have some knowledge of previous formats, I don’t feel qualified to talk about the game since its early years.

Second, Black and White was, in many aspects, a new start for Pokémon. This is not limited to the TCG: Unova was based on the United States, far away from Japan on which Kanto, Johto, Hoenn, and Sinnoh were based, which already put some distance between this generation and the previous ones. The Unova Pokédex featured no Pokémon from previous regions, and even classic Pokémon were replaced: Woobat and Roggenrola replaced Zubat and Geodude as the Pokémon in every cave, etc. There was a desire to go back to the series’ roots and make everything new again rather than build on familiarity.

This resonated in the TCG: Poké-Powers (who could be activated: think Jirachi‘s Stellar Wish) and Poké-Bodies (passive abilities, like Mewtwo and Mew-GX‘s Perfection) were combined into Abilities. The text on cards became simpler, I believe, as a way for designers to get more control over the game. Instead of printing a bunch of cool effects and having players figure out which were the best, they allocated power to some specific cards, and the others had simpler text. This way, they could focus on a few cards they wanted to make the game about, and be sure that these cards would be successful, without being overshadowed by others. This is why it is at that time that the competitive metagame started being molded according to the designers’ wishes, and why if you’re talking about design, Black and White makes a perfect starting point. It’s no coincidence that the Expanded format starts there.

Before the fifth generation of Pokémon, Legendary Pokémon didn’t have a special status in the TCG. Dialga and Palkia had cards in the Diamond and Pearl set, but these cards were not given more attention than other Pokémon. Black and White changed that. Reshiram and Zekrom were the “box legendaries”, they represented the Pokémon Black and White Video Games, so they had to become the focus of the set, and the game. For the first time, we had 130 HP Basic Pokémon, with attacks that dealt 120 damage; almost, but not enough to KO each other. They also shared the Outrage attack, which made sure that if the other Pokémon hit them with a 120 damage attack without using PlusPower or some other damage modifier, they would get KO’d back. Zekrom and Reshiram also both had Energy acceleration available to them thanks to previously printed cards: the combination of Pachirisu and Shaymin, and Typhlosion Prime, respectively. As a result, both quickly became the focus of tier 1 decks.

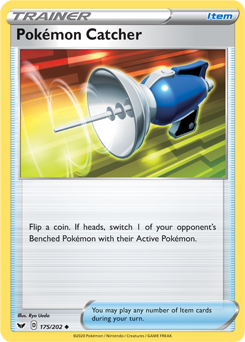

It’s worth noting that at this time, Evolution decks strongly decreased in power. The new turn 1 rules stated that the player going first could both attack and play any Trainer cards they wanted, so it was possible for Zekrom to OHKO any evolving Basic on turn 1. The Rare Candy errata meant that Evolution Pokémon had to wait before coming into play, and the release of Pokémon Catcher in Emerging Powers made it easy for decks to target these Basic Pokémon before they evolved. These changes were also part of a larger plan to make the TCG resemble the Base Set era, another way in which Black and White represented a new beginning (for example, Pokémon Catcher was essentially Gust of Wind).

That said, Evolutions were not out of the game by any means. Reshiram was combined with Typhlosion Prime. Gothitelle was a popular Pokémon because its Item lock prevented cards like Pokémon Catcher and PlusPower, and its HP left it out of reach of both Zekrom and Reshiram. Magnezone Prime was still a strong attacker and draw engine, often combined with Yanmega Prime. The release of Noble Victories brought even more Evolution Pokémon to the metagame, including Chandelure, which doesn’t read anything like a card that would dominate the game, but was (an important factor to its success was Tropical Beach, though, one card that I’m pretty sure was an accident; Worlds promos were supposed to be harmless cards, but no one anticipated how good this draw effect would be for slow decks. Even players took months before they realized the card helped every Stage-2 deck).

Then Next Destinies came out. This was the set that introduced Pokémon-EX, big Basic legendary* Pokémon with a ton of HP and impressive attacks, that gave two Prizes when KO’d. The star of the set was Mewtwo-EX, a card that was definitely designed to dominate the game. X Ball was effective against everything; put enough Energy on a Mewtwo-EX, and it will KO anything. The best counter to Mewtwo-EX was another Mewtwo-EX. If one Mewtwo-EX has three or more Energy on it, another Mewtwo-EX with a Double Colorless Energy will OHKO it, thanks to its Weakness. If both Mewtwo-EX have a Double Colorless Energy, X Ball deals 160 HP; just short of a KO, unless you use PlusPower.

This led to the dreaded ‘Mewtwo Wars’, one of the dullest eras of modern Pokémon. Good decks used Mewtwo-EX and some form of Energy acceleration (Celebi Prime, or Eelektrik) both to deal more damage and to counter the opponent’s Mewtwo-EX.

Mewtwo-EX’s importance started to decay over the rest of the Black and White era, but pretty much every playable deck was centered around one or several Pokémon-EX. Most decks used one as a main attacker, and an Evolution as support, usually for Energy acceleration: Rayquaza-EX / Eelektrik, Darkrai-EX / Hydreigon, Keldeo-EX / Blastoise, etc. Some other decks managed to even get rid of Support Pokémon and simply use main and secondary attackers: Darkrai-EX / Terrakion, various Landorus-EX decks, Virizion-EX / Genesect-EX.

Since most of these decks played in similar ways, how did they differ from each other? What made a player want to play one instead of another? By how they interacted with each other. The Black and White era started the idea of having each set introduce cards that counter the dominant archetype from the previous set, mostly due to Weakness and Resistance. Darkrai-EX resisted Psychic, allowing it to handle Mewtwo-EX. Landorus-EX was effective against Darkrai-EX. Keldeo-EX would easily one-shot Landorus-EX**. Genesect-EX beat Keldeo-EX.***

* Until Legendary Treasures, the last set of the Black and White era, Pokémon-EX were all legendary Pokémon. The fact that there existed enough legendary Pokémon to print six to eight Pokémon-EX per set for two years is a topic for another rant.

** Landorus-EX and Keldeo-EX came out at the same time, so I’m cheating a little bit here. The overall point stands, though.

*** Eternatus VMAX beats Dragapult VMAX, Coalossal VMAX beats Eternatus VMAX. This design philosophy is still a part of the game nowadays.

If the metagame was focused so much on Pokémon-EX, it wasn’t only because of the Pokémon themselves, but also because of the Trainer cards available in the format. There was little Pokémon-based draw: most of the time, you’d draw cards with Professor Juniper and N. This rewarded aggressive play, decks in which you’d throw away your all hand in order to try to draw into the Double Colorless Energy that would allow your Mewtwo-EX to KO the opponent’s Active Pokémon, or the Pokémon Catcher to take an easy KO on a Benched one. When the game favors drawing random cards rather than searching for specific ones, its harder to use combinations of cards, even one as simple as Rare Candy and your Stage-2 Pokémon. When discarding your whole hand to use Professor Juniper on turn 1 is common, you’ll often have to discard Evolution Pokémon that you can’t play yet, which is an issue that you wouldn’t have if your deck only played Basics.

With Legendary Treasures came two changes that helped to set the stage for some changes: Pokémon Catcher was errata’d to the text we know today, and the player going first was no longer allowed to attack. Since there were no good Evolution attackers in the format*, the game still revolved around big Basic attackers, though.

* apart from Empoleon, but apparently I’m not supposed to praise Empoleon in every single article I write.

The XY era didn’t do anything amazing at first. The Fairy type was introduced, and therefore it existed in the game, but it had no specific identity (a shame, since the introduction of a new type, could have been the right time to give each type its specificities). Then, Seismitoad-EX came out: a 180-HP basic attacker that, for one Double Colorless Energy, dealt 30 damage and prevented the opponent from playing Items on their next turn. This card changed the game… but not immediately.

It was obvious it was good, but in a world where cards like Black Kyurem-EX could deal 200 damage in one attack, 30 damage was pretty low. Except that Black Kyurem-EX needed Blastoise, and Blastoise needed Rare Candy, and you couldn’t use Rare Candy when Seismitoad-EX was hitting you turn after turn. Slowly, Seismitoad-EX quaking punched some strategies out of the game. Stage 2s couldn’t really be played anymore. While that specific result is not something I would usually praise, I believe that Seismitoad-EX was, overall, a force for good. Games take longer when they revolve around a 30 damage attack than around OHKOs, which means that players get to draw more of their decks (so the one who built it better tends to win, with lower variance) and that they get to make more decisions during the game. Seismitoad-EX ended up making the format revolve around it, but along the way, it managed to phase out the previous era of boring decks and lead the way into a new era.

The XY era, to its credit, managed to bring more originality in the game. Phantom Forces was perhaps the strongest set overall since Black and White, and not all of these powerful cards were new ideas (Bronzong was a type-shifted Eelektrik), but it showed a new side of what the Pokémon TCG was about. Battle Compressor and VS Seeker let players use the discard pile as a resource like never before, and were a good fit for strategies such as the aforementioned Bronzong. There were playable Mega Evolutions, there was a Crobat line that could put a lot of damage on the opponent’s board, there were Tools that you would play on your opponent’s Pokémon to weaken them… and there was Night March.

Before Phantom Forces, non-EX Basic Pokémon were not main attackers. They could be Energy accelerators (Yveltal, Xerneas), secondary attackers (Bouffalant), or find some other support role (Sableye), but they didn’t deal massive damage. The closest they got to the role of main attacker was Kyurem in Plasma decks, but not all Plasma decks used Kyurem, and Kyurem wouldn’t OHKO an Pokémon-EX (Weakness notwithstanding). Night March was the first time a non-Pokémon-EX could be used as the main attacker, and OHKO even Pokémon-EX for the single cost of a Double Colorless Energy, with no further Energy acceleration, required. The only cost it paid for this is having low HP on its attackers.

It was also not an especially good deck. At the same time, Phantom Forces gave players ways to use the discard pile, it gave them a way to directly counter these strategies, in the form of Lysandre's Trump Card, a direct counter of Night March. It’s only at the end of the 2015 season that Lysandre’s Trump Card was banned, and Night March became a powerhouse until it rotated. Still, even before that, it was playable, even though it was categorized as a fun deck.

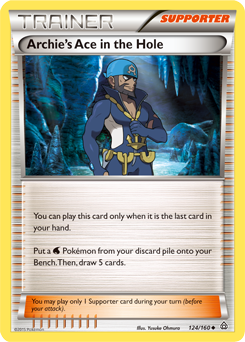

The next sets followed this idea of giving players fun, new, powerful cards. Primal Clash had Archie's Ace in the Hole and Maxie's Hidden Ball Trick, cards with the unique effect of putting powerful Pokémon, even stage 2s or Mega Evolutions, directly into play, even on the first turn, although you needed to build your deck with them in mind (and become adept at sequencing your turn in order to get your hand to 0). Roaring Skies let players have eight Pokémon on their Bench (Sky Field). Ancient Origins let them evolve their Grass Pokémon on the first turn (Forest of Giant Plants, R.I.P.)

It seemed the designers’ imagination couldn’t sustain itself indefinitely, though, and eventually printing cool cards that happen to do powerful stuff gave way to printing powerful stuff period. Breakpoint‘s strongest card was Max Elixir, an Item that encouraged players to play a lot of Basic Energy in their decks, and rewarded them by making their powerful big Basic attackers faster — a concept that would have been right at home in Dragons Exalted or Plasma Storm.* It didn’t show up that much, though, because by the time Breakpoint was released (in 2016, in the XY-on format), you were either playing Night March, one of three flavors of Item lock, or Greninja BREAK.** Decks were extremely powerful at this point in time, but many of them were powerful only because they inhibited the others’ power through some form of lock. Decks that didn’t do that lost to Night March (strangely enough, in a world with Trevenant, Vileplume and Seismitoad-EX, Night March elicited the most complaints).

* In fact, Max Elixir is an actually good variant on Ether, a card from Plasma Storm.

** Greninja BREAK was actually a good example of “printing strong, fun new cards”. It was a perfectly fine deck at the time it was released, and it fitted well in the metagame. It only became a problem in later seasons, when the deck lost consistency and its games were reduced to three possible outcomes: winning because the opponent can’t do anything, losing because you bricked, or losing because the opponent plays Giratina.

Then came the 2017 rotation (Primal Clash-on), and with it, the modern era of Pokémon, defined as the one with the new tournament structure, including International Championships. With no Trevenant, Seismitoad-EX, or Night March in the format, completely new decks appeared; with no good Tool removal, Garbodor became the new center of attention. This is when Max Elixir started to be played everywhere: Yveltal-EX / Garbodor dominated the first International Championship ever, but later on, in the format, it was discovered that Darkrai-EX was even better (mainly because it used Max Elixir more consistently). Both Darkrai-EX and Volcanion-EX made heavy use of Max Elixir, along with a consistency engine using Hoopa-EX and Shaymin-EX and Item cards such as Trainers' Mail and VS Seeker. It wasn’t unusual for decks to play around 25 Items, which is why Vileplume made a big comeback when Sun and Moon was released and it finally found a strong partner in Decidueye-GX (and, of course, Forest of Giant Plants). That wasn’t enough to stop Volcanion-EX or Darkrai-EX from being played, though, and both these decks could still beat Vileplume by playing half their decks and getting a bunch of Energy in play before the Item lock came in.

Compared to the previous two generations, Sun and Moon put a lot more emphasis on Evolution Pokémon. Pokémon-GX replaced Pokémon-EX, and unlike them, they could be either Basics or Evolutions. Professor Kukui wasn’t a reprint of Professor Juniper or Professor Sycamore, but a new effect that didn’t encourage players to throw away their hand. Evolution Pokémon could have powerful effects, Decidueye-GX being the first of many examples. This can be attributed to Solgaleo and Lunala, the “box legendaries” for the seventh generation, being Evolution Pokémon instead of Basics. Therefore, the game had to be more welcoming to Evolution Pokémon, so that they could make a splash in the card game like Zekrom, Reshiram, Xerneas, and Yveltal before them (this specific objective was a complete failure. Lunala-GX never saw any serious play. Solgaleo-GX did, three years later, in one specific rogue archetype, and only because, due to a technicality, it’s still Standard legal outside of Japan).

Despite all that, it wasn’t the Sun and Moon set that changed the game, but its successor. Guardians Rising had the right cards to correct the issues in the previous metagame. Garbodor severely punished archetypes that used too many Items. Unlike Vileplume, you couldn’t outspeed it: if you played half your deck on turn 1, that meant that Garbodor would OHKO you for one Energy on turn 2. Its simple presence made decks like Darkrai-EX and Volcanion-EX either disappear or radically reinvent themselves. Tapu Lele-GX gave decks consistency as well as an efficient, but not overwhelming, attack. Since it could search for Brigette, Evolution decks could use Tapu Lele-GX (expending only one Ultra Ball) to start setting up on turn 1, instead of having to discard their whole hand. After a short time being absolutely dominated by Drampa-GX / Garbodor, the metagame adapted and slowed down.

From then on, Evolution decks found a place in the metagame. Gardevoir-GX won Worlds, then the reign of Zoroark-GX started. While Zoroark-GX did warp the metagame around it for a long time, plenty of other decks were played as well — Zoroark-GX wasn’t stronger than everything else, but it had the ability to adapt to the changes in the metagame in order to beat what was played. Other Evolution Pokemon, including attackers such as Lycanroc-GX, Banette-GX, and Jumpluff, were also played until Team Up came. Instead of Pokémon-GX that could be any Evolution stage, Team Up emphasized Tag Team Pokémon, which were once again big Basic Pokémon with powerful attacks, but with even more HP and more damage. This broke the balance that had been established, and the format went back to being dominated by Basic attackers, with the only exception being Zoroark-GX, until its last stand. That covers the game until the 2020 rotation.

Three Good Formats

In order to understand what makes a format good, I would like to focus on three specific formats that are generally considered to be good: HeartGold SoulSilver to Noble Victories (HeartGold and SoulSilver–Nobel Victories, Winter 2011-12), Primal Clash to Guardians Rising (Primal Clash-Guardians Rising, Summer 2017) and Sun and Moon to Lost Thunder (Sun and Moon-Lost Thunder). In each case, let’s try to figure out what makes people come back to these formats.

HeartGold and SoulSilver-Nobel Victories‘s appeal, I think, is the wide range of different strategies that could be used. It’s not only that there are many viable decks, it’s that these decks all do unique things. For example, Durant was a Mill archetype, that won by actively discarding the opponent’s deck. This is something that had only rarely been seen in the Pokémon TCG, and wouldn’t be a part of the metagame again until 2020.

Magnezone Prime / Eelektrik emphasized resource management. You took Prizes with Magnezone Prime’s excellent Lost Burn attack, but it meant getting rid of Energy permanently, so you had to plan the way the game would go and decide when to KO the Active Pokémon, and when to go for an easier target on the Bench or to use a secondary attacker such as Zekrom. Thanks to Magnezone Prime’s Magnetic Draw and cards like Twins, it was easy to draw into any card you wanted, but you still only played 14 Energy cards. If you used Lost Burn too carelessly, you would end up with no way to win the game. Resource management was a common part of the game before Black and White, but it became rare during that era, as the game tended to reward tempo instead, because of powerful draw effects such as Professor Juniper.

Control decks were not a part of the game for a long time, but HeartGold and SoulSilver-Nobel Victories had the Chandelure archetype which was exactly that: Item lock your opponent (and yourself) with Vileplume, use Chandelure to spread damage counters and draw with Tropical Beach. This deck could use Lampent‘s Luring Light or Smoochum‘s Energy Antics to punish an opponent’s plays and prevent them from attacking and had win states (situations in which the game was unlosable) similar to what can happen in a game of Pidgeotto Control.

Beginners who wanted a simpler deck to play could pick up Reshiram / Typhlosion Prime, a simple Basic attacker and Stage-2 Energy acceleration combination. Those who enjoyed a gamble might like ‘CaKE’ instead, which used the faster but riskier Electrode Prime (combined with Twins) to power up anti-meta attackers like Cobalion and Kyurem. Basically, no matter your playstyle, there was a good deck you could play.

Primal Clash-Guardians Rising, as I mentioned in the previous section, came after a long period of Item-heavy, all-in on turn 1, Pokemon-EX-based decks, in which many players were frustrated because the opening coin flip, or whether you could play enough Max Elixir and thin your deck of Items before your Vileplume opponent establishes Item lock, could decide a game. Suddenly, it was possible to punish these kinds of decks, thanks to Garbodor, and I think this appealed to many, many players. Drampa-GX / Garbodor, and to a lesser extent Espeon-GX / Garbodor, had an amazing showing at the first US Regionals in this format: 24 out of the top 32 decks featured Garbodor, which had many players calling for a ban. However, Garbodor was only devastating insofar as players still played like it was Primal Clash-Sun and Moon. Once people got used to the raw power of Garbodor, they learned how to build their decks around it. Volcanion-EX decks changed their approach and some even stopped playing Max Elixir; in a vacuum, these incarnations of Volcanion-EX were worse than the ones that came three months before; however, in the context of the metagame, they were better. A format that manages to contain a deck’s power this way (even providing Turtonator-GX as a palliative to help with Volcanion-EX’s dependency on Energy acceleration) is doing something right.

Of course, the format didn’t end with Garbodor. While Garbodor stayed tier 1 throughout the format’s life (and ended up winning the last event of that format, the first NAIC), which ensured that at no point could Sun and Moon‘s hyper-aggro decks safely come back, other decks appeared to specifically counter Garbodor: Alolan Ninetales-GX and Drampa-GX / Zoroark were two such decks. These decks, in turn, could be punished by new archetypes such as Decidueye-GX / Alolan Ninetales-GX. No matter what deck picked up popularity, there was a way to deal with it. The combination of Tapu Lele-GX and VS Seeker gave a lot of viability to utility Supporters such as Hex Maniac, Professor Kukui, Teammates and Delinquent since it became easy to play them at any point during the game. This opened up a lot of options when building a deck, and it rewarded players that played around these options in-game.

I recently played this format in an online tournament, picking up the same Decidueye-GX / Alolan Ninetales-GX deck that I used to make Top 16 at NAIC 2017. On several occasions during the tournament, I got punished because my opponent played Hex Maniac, which meant that I couldn’t use Decidueye-GX’s Ability to pick up an important KO. Had I practiced more, I probably would have planned my turns differently and made sure that my opponent couldn’t stop what I wanted to do with a simple VS Seeker for Hex Maniac. Losing because you made a misplay that your opponent capitalized on is a much better feeling than losing because your opponent ended up getting everything they needed after they drew twenty cards, or because they flipped heads on a Pokémon Catcher because it shows you the way to become a better player.

As for Sun and Moon-Lost Thunder, it had a diverse metagame right off the bat. Zoroark-GX, which had suffered from a lack of consistency ever since Brigette rotated, gained Professor Elm's Lecture to replace it and found play alongside either the new Alolan Ninetales-GX and Decidueye-GX or good old Lycanroc-GX (some players preferred using Lillie and more Balls to search for Pokémon, though). Fans of fast, aggressive strategies could enjoy Blacephalon-GX / Naganadel, but those who preferred an emphasis on Bench damage could choose Buzzwole-GX / Lycanroc-GX / Alolan Ninetales-GX instead; and if you wanted your attackers to be non-GX, you had Lost March. If you’d rather focus on a more Toolbox type of play, Tapu Koko / Passimian was capable of rushing down a Zoroark-GX opponent or spreading damage to play from behind with Counter Energy and Tapu Lele. Stall was around (now with Unown HAND as a win condition), Zoroark-GX Control was around, and stage 2s were around because Gardevoir-GX countered many of the previous strategies. The fun new deck to play was Granbull, a unique concept in which you’d get your hand down to zero cards each turn in order to use a one-Energy 160 damage attack, then use Magcargo and Oranguru in order to actually play your deck and not have to pray for a good topdeck.

Like the two previous formats, Sun and Moon-Lost Thunder was diverse, but it’s worth mentioning that some decks were simply fun to play. To me, Granbull is reminiscent of Primal Clash and its Maxie's Hidden Ball Trick and Archie's Ace in the Hole Supporters in the way it requires and rewards precise technical play, and that appeals to a lot of players. An important part of the format was Alolan Ninetales-GX, which was played in Gardevoir-GX, Buzzwole-GX / Lycanroc-GX, some Zoroark-GX variants, and many rogue decks. Alolan Ninetales-GX is simply good design: its a powerful card that’s fun to use because it gives you a lot of choices, and it guarantees you get to use specific combinations of cards that you put in your deck (such as Rare Candy and Timer Ball, or Custom Catcher and a second Custom Catcher). Once in play, it has an efficient, but not overpowered, attack, and a situational GX attack (that was mainly used against Blacephalon-GX).*

* This description also fits Tapu Lele-GX and Zoroark-GX.

Evolution

What do these three formats have in common? What is the thread linking them that explains why they’re better than others? In my opinion, there are two important factors:

- Each of these formats has many viable decks, and these decks scratch different itches. It’s not enough to have several decks, they need to cover various play styles: fast decks, slow decks, control decks, lock decks, etc. This has two benefits: first, it allows players to play the type of deck they like the most; and second, it also means that in any given tournament, players will face different decks, and therefore have a varied experience. Ideally, these decks don’t have too many cards in common, so that even if you can’t afford a staple, you can build another deck that doesn’t use it.

- Each of these formats also rewards skill (both deck building and playing, although sometimes one more than the other). No one likes a format where games are decided by a coin flip or one where you can be out of the game on turn 2 because you can’t play any of your cards. Having some variance is fine, and even arguably desirable so newer players can have a chance against more experienced ones, but too much is annoying, both for the loser and for the winner (I once played Seismitoad-EX / Giratina-EX and won a series where I hit twelve heads out of thirteen on my various flippy cards. I didn’t feel a lot of pride afterward). Losing to Pokémon Catcher feels much worse than losing to Custom Catcher, but it’s not only that. Building your deck around Custom Catcher is more interesting. You can think of combinations with Oranguru, or include cards like Volkner that can search for it. Maybe there’s a tradeoff: I don’t particularly want Jirachi in my deck, but if I don’t use it, I can’t play Custom Catcher. With Pokémon Catcher, there’s no such decision to make. You can add it to your deck regardless of what else is in it. That’s why the game is much better with Custom Catcher in the format than with Pokémon Catcher.

To some extent, maybe a format that doesn’t do well on one of these axes can still work if it’s strong on the other one. I’ve been told that in 2009, for most of the season, the vast majority of games were Gardevoir / Gallade mirrors, but that these were so skill-intensive that the format was better to play than 2012, for example. Assuming that’s true, it’s still worth pointing out that when people play old formats, they rarely go for that specific time. Expanded has the opposite issue: it has a lot of playable decks, but often, games get decided by who gets to achieve their complicated combo first, with few opportunities to outplay the opponent. The ban list helps to keep degenerate strategies at bay, but it seems that some always manage to slip through the net. Expanded has its fans, but most people don’t consider it an example of the best Pokémon has ever had to offer.

That’s not all, though. Comparing each of the three formats above with the ones that came immediately before and after (the most similar formats), I noticed something: in each case, the format that was praised the most was the one where Evolution Pokémon played the biggest role — not only as Support Pokémon but as attackers as well.

HeartGold and SoulSilver-Nobel Victories had the Evolution decks of its predecessor HeartGold and SoulSilver-Emerging Powers, but it also had Chandelure, Eelektrik decks, and more. It was also much better than the Mewtwo Wars format that came after, which was completely focused on Basic Pokémon (and one specific Basic Pokémon, for the most part). Primal Clash-Guardians Rising featured far more Evolution Pokémon than Primal Clash-Sun and Moon because Garbodor slowed the format to a point where slower decks had room to breathe and set up their game, instead of being smothered by the previous format’s degenerate strategies, and the new GX mechanic also introduced powerful Evolution Pokémon. Primal Clash-Burning Shadows… was actually as Evolution-focused as Primal Clash-Guardians Rising, but it was also a great format. The reason why Primal Clash-Guardians Rising stands out more in our memories was that Primal Clash-Burning Shadows was only played for Worlds 2017, whereas Primal Clash-Guardians Rising saw months of play. It’s possible that, had we got more time to enjoy Primal Clash-Burning Shadows, we’d have found it even better.

Sun and Moon-Lost Thunder, like HeartGold and SoulSilver-Nobel Victories, came just before the introduction of a new type of powerful Basic Pokémon that would take over the game. Compared to its predecessor Sun and Moon-Celestial Storm, Sun and Moon-Lost Thunder had more powerful Evolutions. Alolan Ninetales-GX made Stage-2 Pokémon playable again by giving them easy access to Rare Candy, to the point where a deck using three different Stage-2 Pokémon, all of which could attack, won a Regional Championship! Team Up would ruin this and suddenly relegate Alolan Ninetales-GX from a format staple to a forgotten card: Pikachu and Zekrom-GX and Jirachi / Zapdos both shut down these Evolution decks (the first by being able to easily one-shot even Gardevoir-GX, so the effort and resources invested in setting up a Stage-2 were not worth it; the second by being so good at relentlessly targetting low HP Pokémon on the Bench that it made playing several Evolutions a liability).

It’s not that having good Evolution Pokémon in the format suddenly and magically makes a format enjoyable. A lack of playable Evolution Pokémon isn’t the cause of a bad format, but its usually a symptom.

I enjoy playing the current Standard format (Ultra Prism to Rebel Clash). There are several strong decks, and for the most part, they have close matchups, so building your deck with the right techs is important. However, these decks are not so different from each other. Out of the five top decks (Dragapult VMAX, Combo Zacian V, Pikachu and Zekrom-GX, Blacephalon, and Spiritomb / Ultra Beasts), only one plays any Evolution Pokémon (even as support). The others differ by whether they go for OHKOs or 2HKOs, whether their main attacker gives up one, two, or three Prizes, and the specific Support cards they need (Welder for Blacephalon, Jynx for Spiritomb, etc.). None of them gives up Prizes to play from behind, none of them uses a hit and run strategy where they hide behind some kind of wall, they’re simply various efficient attackers and their support staff.

Evolution Pokémon tend to be the ones that let the game be really unique. Unlike many TCGs, there’s no mana equivalent in Pokémon, no resource that dictates which cards can be used early and which ones need more time (there is the Energy system, but Energy acceleration is so widespread that the Energy cost of an attack isn’t a good measure of whether it can be used quickly or not). Instead, Pokémon has the separation between Basic and Evolution Pokémon. Basic Pokémon will attack faster, Stage-1 Pokémon will require more time and cards to set up, but do more powerful things when set up, and that goes double for Stage-2 Pokémon. Greninja BREAK can take multiple KOs in one turn by dealing damage to Benched Pokémon as an Ability, Magnezone Prime, and Zoroark-GX have powerful built-in draw abilities, Gardevoir-GX can build up to unlimited damage and recover resources once per game, etc. When Basic Pokémon can easily OHKO anything in the game, and they have the most HP of all Pokémon, what’s left for Evolutions to do? What’s left for anyone to do, except OHKO the opponent and get OHKO’d in return?

The most diverse formats, those with many different decks that do wildly different things, will always feature Evolution Pokémon, and more specifically Stage-2 Pokémon, because having both Basic decks and Evolution decks will make the game more varied than only having only Basic decks. If you were to design a format with vastly different effects, it makes sense for some of them to go on Stage-2 Pokémon, so that they can be more powerful, but harder to achieve.

Evolution decks are also slower than Basic decks, which is a good thing in general for the game. In longer games, there are more choices to make, more opportunities to outplay the opponent, and less chance of losing because you whiffed an important card on one turn, because when there are more turns, each turn has less of an impact on the overall outcome of the game, on average.

Looking Forward…

What does this mean for the future of the Pokémon TCG?

Obviously, I can only guess based on the current trends of the game. If you’re reading this in 2021 or later, you might find that this section aged terribly (or maybe you’ll think I’m a prophet, who knows).

Right now, Evolution Pokémon are coming back in a big way, but only as VMAX Pokémon. I’m not a big fan of this concept: three-Prize Pokémon tend to polarize the game, and they make it impossible to print powerful defensive strategies (imagine Dragapult VMAX playing Max Potion). Still, they’re technically Evolution Pokémon, and they’re powerful: Dragapult VMAX is one of the best decks of the format. I also find it more interesting to play than other top decks, because placing damage counters on the Bench is fun and, if you think ahead enough, you can be rewarded with blowout turns in which you win the game by taking five Prizes in one turn.

On the other hand, playing Dragapult VMAX doesn’t feel a lot like playing an Evolution deck. Sure, you can’t attack on turn 1, but you’re not doing that with Zacian V or Blacephalon decks either (most of the time). You can’t get by with only playing Quick Ball, but Dragapult would play Mysterious Treasure even if all its Pokémon were Basics, so being an Evolution doesn’t affect the deck building process. Dragapult VMAX being an Evolution means it requires a bit more setup and uses more deck space, but the deck is not particularly slower than any other deck: in most games, you’ll use Max Phantom every turn starting with the second.

If the Pokémon TCG designers learned from Guardians Rising or Lost Thunder the lesson that focusing on Evolution Pokémon was good and applied this lesson by designing the VMAX mechanic, then they’re terribly misguided. Not only have they abandoned a part of the Evolution mechanic (Stage-2 Pokémon!), but they’ve also forgotten to give them Abilities.

Abilities make the game strategic since they give each player more things to do. If you’re building an Evolution deck (think about Zoroark-GX or Gardevoir-GX), then you’ll have many Evolution Pokémon in play. If these Evolution Pokémon don’t have Abilities, then you won’t have many things to do with them, which is wrong: Evolution Pokémon take more space in the deck, and more time to set up, than Basic Pokémon, so if a player puts in the effort to use them, they should be rewarded for it with more options. (Gardevoir-GX was so great to play in the Worlds 2017 format because you could end up with a board with two Gardevoir-GX, a Gallade and an Octillery, and not only is that strong, it’s also super satisfying to play with).

Every slow (relative to its competition) Evolution card I’ve praised (Magnezone Prime, Chandelure, Empoleon, Zoroark-GX, Gardevoir-GX…) has an Ability. Playing Zoroark-GX is fun because you get to draw six cards every turn, and it’s strategic because drawing all these cards gives you access to the techs you put in your deck, so you can afford to run more one-ofs and situational cards. It also provides a pay-off for building a board full of Evolution Pokémon. Good Evolution cards that don’t have an Ability need to have a great attack instead, usually one you build a deck around, such as Vespiquen‘s Bee Revenge.

So far, no VMAX Pokémon that has been revealed has an Ability. This probably means that they’re designed to be played alongside Basic Pokémon with Abilities: for example, a typical Dragapult VMAX board features two Dragapult VMAX and four Basics with Abilities. This makes VMAX decks much closer to Basic decks than classic Evolution decks, though.

Apart from VMAX Pokémon, the most striking thing about the Sword and Shield generation is how much it recycles ideas from XY. Boss's Orders is Lysandre. Eternatus VMAX is M Rayquaza-EX with built-in Sky Field, and Crobat V is its Shaymin-EX. Vikavolt V replaces Seismitoad-EX, and Night March got recycled as Mad Party. The XY era wasn’t the highest point of the game in my opinion, but it had the merit of pushing the envelope with new ideas. Sword and Shield, instead, is extremely conservative, only reusing proven concepts in the safest way possible. Look at Gardevoir VMAX. It might be good, but it’s not exciting.

…And Looking Back

What’s frustrating about this state of affairs (and at the same time, what gives me hope for the future) is that the Pokémon TCG has the potential to do so much more, to be so much more.

My first competitive season was 2010-2011, in the Majestic Dawn-on format. Most of the cards in the format were from the Diamond and Pearl era, which was a high point of the game. Take a look at Stormfront: out of its 31 rare and holo rare cards, 23 of them feature a Poké-Power or Poké-Body, and only four of them have a vanilla attack, that is, an attack with no text (only damage). This was in an era when cards usually had three features, so even cards that had a vanilla attack would also have another, more complex attack, as well as a Poké-Power or Poké-Body. Note that all of these cards except one were Evolution Pokémon. I think that many players, and not only beginners, opened a booster pack of Stormfront at some point and tried to build a deck around the rare card in it — Torterra or Mamoswine or whatever. These didn’t all work out from a competitive standpoint, of course, but some did (hi Gyarados). And even if a deck doesn’t end up being tournament viable, it’s still a good thing when cards get players excited to build new decks.

Compare this with Rebel Clash, the latest set. Out of its 49 rare and rare holo cards (excluding Boss’s Orders), a large majority (40) are still Evolution Pokémon. However, only 18 out of these 49 Pokémon have an Ability, and 20 of them have a vanilla attack. None of them has three attacks (or two attacks and an Ability). The power has been shifted from rare cards to ultra-rares (which happen to be mostly Basic Pokémon, with a few VMAX), and the complexity has been drastically lowered. What is anyone, even a new player, going to do with Abomasnow or Galarian Perrserker?

I won’t talk about the Majestic Dawn-on format in detail, but it had many features that seem impossible today. It had Uxie, a better Shaymin-EX, which was still completely fair because drawing cards with Pokémon rather than Supporters was the norm, and expending one Bench spot for it was a significant cost. It had an Item lock deck which could stop you from playing Items from the very first turn of the game, but which was still fine compared to later incarnations of Item lock because Supporters were search-based instead of draw-based, so you could still achieve your strategy without playing Items, but in a slower way. It had Azelf, which let players tutor a Pokémon from their Prize cards, thus turning Prize cards, a source of randomness (and therefore frustration) by design, into a resource to be used. It had a way for some decks to stop Poké-Powers during their opponent’s turn. Majestic Dawn-on isn’t even that popular as far as retro formats go, because Diamond and Pearl-on was all that, but better.

I’m not going to claim that formats before Black and White were universally better, because I don’t think that’s true, and I didn’t play them so I can’t really argue either way. My point is not that the game used to be better, its that a different game is possible. Someone once argued with me over Twitter that it was pointless to complain when new cards are boring because there’s only a limited number of effects that are possible, so the game will have to repeat itself at some point. This is not true*. The game played completely differently ten years ago, and even in recent eras, we’ve seen unique concepts brought to the game. There’s no reason to expect the game in five years to play the same as today, to accept this status quo.

*Technically it is, since the number of sentences that can be printed on a card is limited, but in practice, there’s still so much design space unexplored that its meaningless.

Some may object that it makes sense for the game’s designers to favor simple cards and concepts. Maybe the game needs to be faster so that Japanese players can play more rounds in their best of 1 tournaments. Maybe having the most powerful cards be flashy, ultra-rare cards with text that’s easy to grasp brings more new players into the game. Maybe the game sold more cards in the XY era so it was deemed profitable to reprint all of its powerful archetypes in hope of finding gold again. I don’t care. I’m not a TPCI employee, so how much a set sells doesn’t matter to me, and if you, a player, argue using a company’s point of view, you’re acting against your own interests. But even taking some logistical constraints into account, things could still be different. If only ultra-rare cards are supposed to get players excited, then they should be more like the HeartGold SoulSilver era’s LEGEND Pokémon: give them a striking visual design, and unique attacks that have never been on any other cards.

And there are many other ways the game could evolve.

A higher focus on Evolution Pokémon, and specifically Stage-2 Pokémon, is necessary to make some slower archetypes and have a more varied metagame.

Making better use out of the Prize cards is also a no-brainer: this is a mechanic that only exists in this game, there’s no reason not to explore it more! Print more effects like Azelf (or Legacy’s Rotom + Alph Lithograph combination) that let you use your Prize cards as a resource. Have attacks like Gallade‘s Psychic Cut that use your Prize cards as fuel. Print common ways to turn your Prize cards face up, then have some Pokémon who have an Ability that works from the Prizes.

Dual-type Pokémon should be a recurring part of the game. Have a dozen Pokémon in each set that have two types, like in Steam Siege. This adds a little bit of originality, some will find uses in competitive play, some collectors would want to get these cards specifically (especially if you give them a cool visual design), and it’s such a simple thing to do that having to expend an Ability to achieve the same result (hello, Gallade) is a waste.

Lock (Item, Ability, whatever) is an important part of the game because, since you can’t meddle in your opponent’s plans during their turns, a good way to do so is to prevent them from using what they need for their game plan in the first place. However, this can often lead to all-or-nothing scenarios, where either a lock is achieved and the other player is miserable, or it isn’t achieved and the lock player is not doing anything. Why not imagine softer forms of lock? Instead of “you can’t play Items from your hand”, try “you can only play one Item from your hand per turn”. This way, a player that desperately needs to play Ultra Ball to draw cards can still do so. The Item lock will slow them down significantly, but not completely kill them if they were unlucky enough to draw into a hand full of Items.

New mechanics should be explored. Pokémon that can attach themselves to other Pokémon like Tools, then go back to the Bench once the Pokémon they were attached to is Knocked Out. Pokémon that can be played face down, and are only revealed when they take damage, become Active, or Evolve. Reactive Items or Abilities that can be activated when the opponent uses an attack; by restricting the mechanic of playing cards during the opponent’s turn to the attack phase, it should be fine to implement in TCGO (you don’t need to have players pass priority during their turn, you only need to ask Player B if they want to play something when Player A uses an attack, once per turn).

I’m just throwing out these ideas in the air. Maybe some of them wouldn’t work out, for any number of reasons. I’m sure you have your own ideas about what you’d like to see in the game! The point is that there could be new effects, new mechanics, new strategies.

As it is, the game is fine. It’s fine! It’s serviceable. I’m sure it will stay fine for a long time, because the trend is to safely copy things that have existed before and were fine, without rocking the boat. Each new archetype, I’m sure, is meticulously playtested in order to make sure it doesn’t lead to anything degenerate. And on some level, it’s ok for the Pokémon TCG to be that. It could certainly be worse. However, the past has shown that Pokémon could also be a much more intricate game, so I’m really hoping we will go back to that at some point. And in the worst-case scenario, we will always have Primal Clash-Guardians Rising, Worlds 2010, Legacy, and other good formats.*

* Including some that were never played in a tournament. Does Sun and Moon-Cosmic Eclipse sound cool to anyone else?

This was the longest article I’ve ever written (in English, at least), so if you read it from start to finish, thank you! I’m sure there were things you disagreed with in it, and that’s perfectly fine. As long as this article made you think about the game and what makes it good, it achieved its goal!

If you enjoyed reading this, you might enjoy all the other things I’ve written, because I wrote them too (see? I’m good with words). Usually, there’s decklists and advice to get better at the game as well, so if that sparks your interest, you might want to consider getting a premium membership to get access to all that. It’s fine if you don’t, though! Thanks for reading either way!

–Stéphane